"History of Medicine Book of the Week" is a series featuring blog posts written by students in the course, HIST H364/H546: The History of Medicine and Public Health (Instructor: Elizabeth Nelson, School of Liberal Arts, Indiana University, Indianapolis). The following post is the first in the Spring 2024 series.

Woman, and Her Diseases: From Cradle to the Grave, Adapted Exclusively to Her Instruction in the Physiology of Her System, And All the Diseases of Her Critical Periods (1847), Dr. Edward H. Dixon

By Victoria Bozinovski

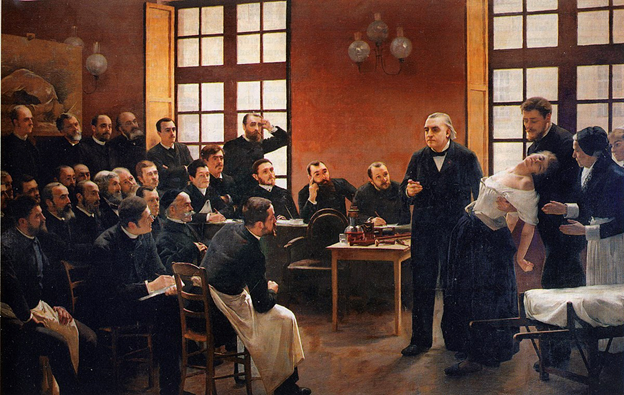

Painting. A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière by Pierre Aristide André Brouillet. Descartes University in Paris (Museum of the History of Medicine), 1887. [1]

The Victorian Era was an interesting time to be a woman. The male perspective ruled and had been ruling for quite some time, especially in medicine, leaving women little space to voice their health concerns. The idea of a woman was often simplified to a hysterical creature in need of a husband and domestic duties to keep her in check. This perspective can be seen in Woman, and Her Diseases, a book by Dr. Edward H. Dixon, an American surgeon. Dixon was born on December 31, 1808, in New York City, NY, with works published from 1842 to 1893 [2].

This volume is a gynecological text that describes the different illnesses a woman can experience, and though the title promises from the cradle to the grave, the text is focused predominantly on childbearing years. Its chapters are divided into individual disorders, in which the typical symptoms are listed, paired with details of how these symptoms are best to be handled by the family and physicians. No, not by the woman herself – that would be absurd – but by others, primarily the men in her life.

Before delving any further into the text's viewpoints, we must consider its context. Woman, and Her Diseases was published in 1851, an era of transition away from miasma and humoral theories of medicine, toward germ theory. These older practices were often paired with the concept of how moral character influenced one’s health, traces of which can be seen in this. However, the book also demonstrated a distinctly clinical approach to the observation of women’s ailments; therefore, for the period, it did its best to apply an objective and clinical perspective to the phenomena occurring in a woman’s body. This makes it uniquely reliable for the time. Dr. Dixon was more known for his dissident views on medicine in general, rather than for his gynecological work, so it was not a very remarkable piece. Dixon stated in the opening passage that his intention in writing Woman, and Her Diseases was “affording woman the means of instructing herself” about her body. He went as far as dedicating the book to “the mothers among my countrywomen.” Dixon claimed the need for this text was to inform women so that they could remain happy and healthy [3].

However, Dr. Dixon viewed women as inferior to men and physicians – which were often the same. Despite dedicating the work and its purpose to the direct education of women about their bodies, Dixon never acknowledged women directly as the readers of the material. For example, in the chapter on hysteria, Dixon explains that the family of the afflicted should physically restrain the woman as a method of preventing a hysterical “attack” [4]. He explains further: in the case of an emergency, a “candid physician will freely communicate to some intelligent member of the family” how to handle the woman’s fits [5]. This assumes that a woman is unable to control herself during a fit of hysteria, and that physicians and family members should step in. This stripped woman of their agency.

There is also a lack of consistency in the symptoms Dixon applied to the condition of hysteria. Most of the other diagnoses he described had clinical support: in the chapter that addressed leukorrhea, i.e. vaginal discharge, he provided clear explanation of the cause of the disease (overproduction of vaginal mucus) and the pathology of the organ structures involved (blood vessels of and around the mucosal membranes of the vagina). Hysteria, on the other hand, had “an infinite variety of symptoms” that only someone who has seen the disease manifested in a large number of individuals can pinpoint. This makes hysteria less clinical and more socially constructed. Many female historians agree that the “Victorian Era was characterized by incomplete, conflicting, or erroneous information about female health and reproduction”[6]. This work was unremarkable but may help to convey a viewpoint of women and their ailments during this era common among doctors like Dixon.

Using works such as Woman, and Her Diseases, we can piece together the overarching historical trends of medicine to inform our treatment of patients moving forward. Since women have historically been ignored and misunderstood, it is important to actively try to correct those biases as we seek to improve medical practices. This will not only limit the clinical mistakes that negatively impact women, but will also help women to have a stronger voice in medicine, as doctors, patients, and participants.

References:

[1] Harris JC. A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(5):470–472. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.470

[2] Kaufman, Martin. "Edward H. Dixon and Medical Education in New York." New York History 51, no. 4 (Jul 01, 1970): 395. https://ulib.iupui.edu/cgi-bin/proxy.pl?url=http://search.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/edward-h-dixon-medical-education-new-york/docview/1297198678/se-2

[3] Dixon, Edward H. Woman, and her Diseases, from the Cradle to the Grave: Adapted Exclusively to her Instruction in the Physiology of her System, and all the Diseases of her Critical Periods. New York: Charles H. Ring, 1847. https://resource.nlm.nih.gov/67020040R

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Newman, Louise Michele. "Health, Sciences, and Sexualities in Victorian America." In A Companion to American Women’s History, edited by Nancy A. Hewitt, 206-24. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2005.