Childbirth without Fear: The Principles and Practice of Natural Childbirth (1944), Grantly Dick Read

By Emily McNally

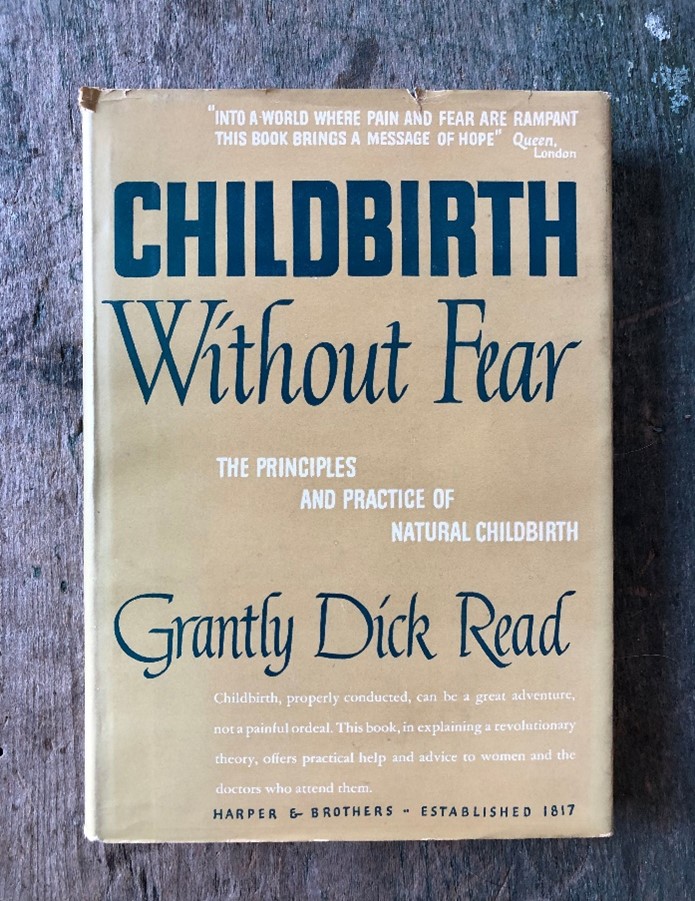

To any twenty-first century woman interested in natural childbirth, one name rises above the rest: Ina May Gaskin (1940–), the famed American midwife. But even giants in the field credit their intellectual predecessors, and Gaskin’s is British obstetrician Dr. Grantly Dick Read. Not only was the name “Dr. Dick Read” synonymous with “natural childbirth” in post-war Britain, but it was also Dick Read who is credited with coining the term [1]. The Indiana University Ruth Lilly Medical Library’s rare book collection contains a 1944 American printing of Dick Read’s seminal work, Childbirth without Fear: The Principles and Practice of Natural Childbirth, first published in 1942 as Revelation of Childbirth. The British Medical Journal came out swinging in its review of the text, calling it a “challenge to obstetricians” and accusatory of “the medical profession in general and the consulting obstetrician in particular” [2] Yet by 1950, a reviewer estimated that “no other medical author had been so extensively read by laymen” [3].

During World War I, Dick Read served with the Royal Army Medical Corps and was badly wounded at Gallipoli. He recovered in a convent hospital, blind in one eye, and retaining only limited, cloudy vision in the other. He recalled that in his convalescence, visitors only made him feel worse with their platitudes and false empathy; and not merely emotionally worse, but physically worse. Their visits made his body tense up, his muscles twitch, and his head throb. Then a nun came to sit with him, in companionable silence, and his muscles finally relaxed. From this experience he reflected, “There is no greater loneliness in the life of a human being than being alone with one’s own suffering; and no suffering is greater than the mental torture of impending agony from which there is no escape and of which there is no understanding.” He brought this revelation with him to his study and practice of obstetrics, as he attended to women experiencing the worst physical pain of their lives [4]. This early work of Dick Read’s was heavily influenced by the work of American physician Edmund Jacobson, who published Progressive Relaxation in 1929 [5].

His thesis of escaping pain and suffering continued to evolve from interactions with patients. He recalled an event where he tried to give chloroform to a woman in labor, but she refused. Afterwards she said to Dick Read, “It didn’t hurt, doctor. It wasn’t meant to hurt, was it” [6]? Dick Read postulated that “somatic or physical changes may occur as a direct result of psychological states.” In lay terms, your mental conditioning prior to labor may affect how you perceive labor and childbirth as causing you pain and discomfort. Fear increases intensity of stimuli, and stimuli almost invariably become represented as pain.

While Dick Read was studying Jacobson and his promotion of progressive muscle relaxation as an antidote to pain, there was a movement among British women advocating that anesthesia be made available to laboring women. The National Birthday Trust (NBT) was formed in 1928 by socially prominent and politically influential women “disturbed by the inaccessibility of obstetric care to poorer classes of British women, particularly the low proportion of women offered adequate relief from labor pain” [7]. The NBT raised money for research to develop anesthesia techniques suitable for midwives to use at home births [8]. Examples of their success included glass ampules containing a measured amount of chloroform and a gas-air apparatus for breathing in nitrous oxide [9]. Consumer demand for labor pain relief soon became part of the larger institutional and social pressures to transform hospital obstetric care.

In hospitals, where the majority of births were occurring by the 1930s, a profusion of sedatives, analgesics, and anesthetics became parts of routine practice [10]. However, at the same time some women were voicing dissatisfaction with hospitalized labor and delivery, which they found alienating and disempowering [11]. Dick Read’s writing resonated in this segment of post-war society that venerated family life and idealized women as homemakers and domestic consumers [12]. This gradual change allowed Dick Read to pursue nontraditional aspects in his recommendations for care of women in labor. Whereas anesthetized hospital births banished fathers to the waiting room, Dick Read held them up as true partners in the prenatal experience. He encouraged them to attend their wives’ birth preparation classes to learn about the anatomy and physiology of the birth process, and to learn breathing techniques and relaxation exercises that could be useful during labor. While this seems like common sense to the modern mother interested in foregoing an epidural, it was a revolutionary practice in its time. Prior to the 1950s, fathers were practically unheard of in the labor room, and newborns did not “room” with their mothers after delivery, but rather were placed with other infants in a communal nursery [13].

For centuries, childbirth had been associated with pain. Dick Read’s idea of natural childbirth was not popular when first expressed, especially among his fellow doctors. He was ridiculed to the point of expulsion from his London practice, despite being a popular care provider among the patients. Indeed, as patients became more enthusiastic about Dick Read’s methods, “many physicians became more hostile” [14]. His colleagues’ pushback was due to their belief that advancement in medical technologies progressed in a linear fashion; to advocate for birth absent anesthesia was to take women’s healthcare backward. Undeterred, Dick Read would go on to set up his own private clinic. Dick Read would never obtain popularity within physician circles, but he did eventually earn a begrudging respect. When the British Medical Journal ran an obituary for Dick Read, they admitted “his views, and the ways he expressed them, gave rise to controversy, but the soundness of many of the principles on which he based his teaching was not in question” [15]

Dick Read says that his work was written for general audiences, for prospective mothers and fathers, as well as healthcare professionals, but sections of the chapters include very technical language about the physical processes that happen at the cellular level when the body experiences fear. I can only summarize as follows: fear leads to tension, and tension leads to pain. A particularly memorable anecdote Dick Read gives in support of this thesis is the observation of an ischemic, or white, uterus: a woman was rushed for an emergency caesarean due to urgent fetal distress. The labor had been inhibited by strong but ineffective contractions. The mother had no physical obstruction, “but uncontrollable fear had caused, through the resistance of the circular muscles, such tension within and ischemia of the uterine muscles that the baby, through excessive intra-uterine pressure and restricted oxygen supply, was unable to survive a protracted labor and vaginal delivery. The white uterus persisted in spite of surgical anesthesia, which demonstrated the depth of fear within the psyche of the conditioned individual” [16]. This mother’s fear of childbirth had manifested on such a cellular level, that the decreased blood supply to her uterus (when we are afraid, fight-or-flight kicks in, diverting oxygenated blood to the parts of the body presumed to do the fleeing or fighting) persisted despite her being under general anesthesia.

In addition to Gaskin, Dick Read’s theory and practice influenced such names as Fernand Lamaze and Robert Bradley, both of whom have methods of experiencing natural childbirth named after them. The methods may differ, but they share Dick Read’s belief that if a woman learns and practices techniques of physical and psychological conditioning, her discomfort during labor and delivery can be lessened, allowing her to become an active facilitator of the birth process.

(This post was written for the course HIST H364/H546 The History of Medicine and Public Health. Instructor: Elizabeth Nelson, School of Liberal Arts, Indiana University, Indianapolis).

References:

[1] Salim Al-Gailani, “Drawing aside the Curtain: Natural Childbirth on Screen in 1950s Britain,” The British Journal for the History of Science 50, no. 3 (September 2017): 474, 476. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5963435/.

[2] “Review: A Challenge to Obstetricians,” British Medical Journal, 2, no. 4264 (September 26, 1942): 368. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20324195.

[3] Al-Gailani, 476.

[4] This was the era when middle and upper-class British women opted for “twilight sleep.”

[5] “Obituary: Grantly Dick-Read, M.D.” British Medical Journal 1, no. 5138 (June 27, 1959): 1625. https:///www.jstor.org/stable/25387931.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Caton, Donald. “Who Said Childbirth Is Natural? The Medical Mission of Grantly Dick Read.” Anesthesiology 84 (April 1996): 955–64. https://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article/84/4/955/35416/Who-Said-Childbirth-Is-Natural-The-Medical-Mission.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Al-Gailani 474.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid., 476.

[13] Caton.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Obituary,” 1625

[16] Grantly Dick Read, Childbirth Without Fear: The Principles and Practice of Natural Childbirth, 4th ed. (London: Pollinger Limited, 1949), 76.