Degeneration and Regeneration of the Nervous System (1913), Santiago Ramon y Cajal

By Erin Delaney

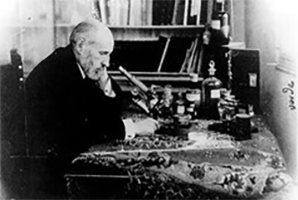

“Every man, if he is so determined, can become the sculptor of his own brain” [1]. These are the famous words of Santiago Ramon y Cajal (1852-1934), the father of modern neuroscience. Most known for establishing the neuron doctrine as well as his masterful drawings of individual neurons, Cajal was committed to understanding the inner workings of the human brain and nervous system. However, he was not only pursuing neuroanatomy but seeking answers to his own emotional and spiritual questions of self-improvement. How did a man’s thought and will manifest itself in the human brain? “To discover the brain,” Cajal said, “was the equivalent to ascertaining the material course of thought and will” [2]. In 1913, Cajal published Degeneration and Regeneration of the Nervous System (original Spanish title: Degeneración y Regeneración del Sistema Nervioso) to better understand what we now refer to as neuroplasticity.

Much of Cajal’s destiny was a product of his father’s unrelenting expectations. As a young boy, Cajal was much more interested in becoming an artist than a physician or scientist [3]. Cajal’s father, Don Justo, treated his son’s artistic impulses as a psychological disease that must be extracted. Determined to have his son achieve a higher social status than that to which he was born, Don Justo sent his young son away to a medical preparatory school where he was subjected to beatings, imprisonment, and starvation as punishment for rebellion [4]. Ultimately, Cajal was forced into submission and became an apprentice to a barber-surgeon where he learned the art of dissection [5].

In 1866, when Cajal was sixteen, he and his father stole a corpse from a nearby graveyard to perform a dissection together. “He suddenly realized that human beings were the most beautiful of all of the objects in nature” [6]. His fate sealed, Cajal enrolled in medical school, applying his inherent artistic spirit as a unique lens to medicine.

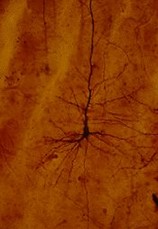

The turn of the century was a time of great innovation in the medical community. Advances in microscopy, histology, and anatomy created windows into worlds once out of scientific reach. In 1873, Camillo Golgi (1843-1926) discovered a new histological stain that revealed much greater detail in nervous tissue that was obscured by prior histological stains. What is now known as the Golgi stain was a complete revelation to Cajal. “Here everything was simple, clear, and unconfused… The amazed eye could not be removed from this contemplation. The dream technique is a reality” [7]! This technique fueled Cajal’s confidence in his development of the neuron doctrine.

Cajal worked tirelessly to convince the scientific community that neurons were individual and separate; but much of his work at the time was either dismissed by his peers or went unpublished. Prior to Cajal’s discovery, the nervous system was thought to have worked similarly to the vascular system; as one continuous flow of electric current throughout the body as proposed by Golgi’s reticular theory [8]. The language barrier inhibited many histologists and neurologists of the time from reading Cajal’s original Spanish publications. In 1888, Cajal became the founder and editor of his own journal called The Trimonthly Review of Normal and Pathological Histology (The Revitas) in order to avoid publication delays [9]. The amount of evidence produced eventually gained the attention it deserved, and in 1891, Cajal fully described the neuron doctrine, which states that the nervous system is comprised of individual neurons that are interconnected by junctions called synapses. This revolutionized the way neuroanatomy was interpreted and studied, solving one of the multitude of mysteries of the brain and nervous system.

In 1899, Cajal produced what many see as his masterpiece, Textura del Sistema Nervioso del Hombre y de los Vertebrados. Originally published in Spanish, this first volume was expanded to three volumes by 1904. Cajal was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1906 for his contribution to the scientific understanding of the nervous system. His Textura del Sistema Nervioso was translated into English in 1913, as The Texture of the Nervous System of Man and the Vertebrates. This title was in direct reference to the pioneer of human anatomy Andreas Vesalius’s 1543 famous work, On the Fabric of the Human Body [10].

With the foundations of neuroanatomy established, Cajal could then focus on exploring the brain’s anatomical response to external traumas. In 1913, he published Degeneration and Regeneration of the Nervous System (Degeneración y Regeneración del Sistema Nervioso). This two-volume work holds a collection of experiments conducted over the span of eight years, containing over eight hundred pages and three hundred illustrations [11]. These studies investigated the nervous system’s unique mechanism of degeneration and regeneration: different types of neurons were exposed to various external traumas in various extracellular conditions, and their respective responses were recorded and interpreted. The findings concluded that regeneration was possible for the neurons in the periphery, but those in the central nervous system needed additional investigation [12]. There is an exciting and anticipatory tone in Cajal’s writings; as one of his disciples writes, “For Cajal, technique and science were the natural, spontaneous result of a secret activity moved by faith” [13].

The major hypothesis Cajal explored in Degeneration & Regeneration of the Nervous System was the idea of neurotropism, the term used to describe the chemical force that drives neurons to display their need for reconnection. It was the absence of this neurotropic factor that explained the differences in behavior between neurons that Cajal observed in his experiments. “The life of a neuron does not obey an immanent and fatal tendency maintained by heredity, as certain authors have defended, but it depends entirely on the physical and chemical circumstances present in the environment” [14]. The theory of neurotropism was initially accepted by Cajal’s colleagues, but was later challenged [15].

Another theory proposed in this text that faced opposition was the axon outgrowth theory. The axon outgrowth theory proposed what Cajal referred to as a “growth cone” on the budding axons that allows them to respond to the neurotropic factor in its efforts to reach the intended target [16]. Curiously, neurons from the central nervous system responded differently than those in the peripheral nervous system. Cajal attributed this difference to the absence of Schwann cells in the central nervous system. He believed that the Schwann cells were responsible for producing the neurotropic factor in the extracellular space.

Amazingly, the theory of neurotropism has been proven credible and is now commonly used in neuroscience medical practice. In 1950, Levi Montalcini performed a series of experiments placing spinal ganglia in what is now referred to as neuronal growth factor (NGF). The results showed profuse growth of fibers from the spinal ganglia after being placed in surrounding NGF. Cajal’s suspicion of this chemical affinity between axons when going through the process of regeneration was confirmed. In 1970, this NGF was also confirmed to be produced by the Schwann cells as Cajal previously predicted [17].

Santiago Ramon y Cajal laid the groundwork for unlocking the vast potential held within the human brain. While Degeneration and Regeneration of the Nervous System was ahead of its time, modern medical science has made vast advances in accessing the activity of the brain and nervous system. These developments allow expanded scientific testing of Cajal’s hypotheses, and history has proven his hypotheses correct. Just as the neuron doctrine allowed for examination of activity in the synapse, we must expand our research efforts to the curious mysteries that were regrettably left unsolved during Cajal’s lifetime. His work is the first steppingstone in the last frontier of our exploration of the inner workings of the brain. The medical community must walk before it can run; with each experiment we get closer to harnessing this momentous knowledge. In Cajal’s parting words just before his death in 1934, he said,

Let us carry on the pursuit of knowledge with the same spirit guiding our search for truth.

This post was written for the course HIST H364/H546 The History of Medicine and Public Health. Instructor: Elizabeth Nelson, School of Liberal Arts, Indiana University, Indianapolis.

References:

[1] Cajal, Santiago Ramón y, and Raoul M. May. Degeneration & regeneration of the nervous system. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1913.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ehrlich, Benjamin. The Brain in Search of Itself Santiago Ramón y Cajal and the Story of the Neuron. New York, NY: Picador, 2023.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ehrlich, Benjamin, and Santiago Ramón y Cajal. The Dreams of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. New York, NY, United States of America: Oxford University Press, 2017.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ehrlich, Benjamin. The Brain in Search of Itself Santiago Ramón y Cajal and the Story of the Neuron. New York, NY: Picador, 2023.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Cajal, Santiago Ramón y, and Raoul M. May. Degeneration & regeneration of the nervous system. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1913.

[13] Ehrlich, Benjamin. The Brain in Search of Itself Santiago Ramón y Cajal and the Story of the Neuron. New York, NY: Picador, 2023.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Cajal, Santiago Ramón y, and Raoul M. May. Degeneration & regeneration of the nervous system. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1913.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ehrlich, Benjamin, and Santiago Ramón y Cajal. The Dreams of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. New York, NY, United States of America: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Image Credits:

Figure 1: “The Black Reaction.” Javier DeFelipe and Ricardo Martinez-Murillo. In Bentivoglio, Marina. “Life and Discoveries of Santiago Ramón y Cajal.” Nobel Prize Outreach, April 20, 1998. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1906/cajal/article/.

Figure 2: “Self-portrait of Cajal at the microscope in 1920.” Javier DeFelipe and Ricardo Martinez-Murillo. In Bentivoglio, Marina. “Life and Discoveries of Santiago Ramón y Cajal.” Nobel Prize Outreach, April 20, 1998. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1906/cajal/article/.