The Toxic Amblyopias: Their Classification, History, Symptoms, Pathology, and Treatment (1896), George Edmund de Schweinitz

By Mikaela Messer

He was born and established a career in Philadelphia, working at the Wills Eye Hospital after he graduated from University of Pennsylvania. Most of his research on toxic amblyopia’s took place at Wills Eye Hospital, where he found subjects to be a part of his studies. In the late 19th century, ophthalmologists wanted to understand the human eye better and identify which specific toxins impaired vision. This is when de Schweinitz’s work emerged, and he contributed an abundance of valuable insights for classification, history, symptoms, pathology, and treatment in the field of ophthalmology.

A toxic amblyopia reduces vision in one or both eyes due to exposure to toxins such as alcohol, tobacco, and chemicals. This amblyopia usually happens because the eye does not properly develop during childhood, a condition that was more common in the 19th century the lack of regulations imposed by the government on consumer products. For example, the age limit regulation for alcohol consumption nor the effects of alcohol consumption by pregnant women had not been established yet. During this time, vision health for children was affected by toxins such as alcohol, intestinal parasite expulsion, chloroform, and marijuana. De Schweinitz researched many other toxins such as lead, arsenic, and mercury.

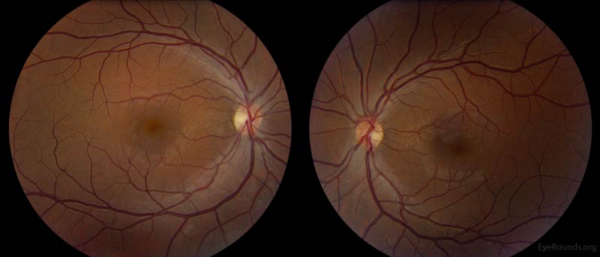

De Schweinitz's alcohol toxin study examined ten cases in total, including people, rabbits, and dogs, to see if lesions appeared on their optic nerves after they ingested an excess amount of alcohol. De Schweinitz found that there are two factors that cause alcohol poisoning and, in turn, blindness or correlated eye problems: consuming a lot of alcohol for a long time and fusel oil present in the alcohol. The only cure was abstinence from alcohol. Figure 1 is a modern image showing the effect of chronic alcohol abuse causing temporal pallor, whiteness, on the optic nerve.

De Schweinitz was presented with many awards for his achievements from esteemed members of the ophthalmology world. He was awarded the Howe Metal in 1926 by Walter Parker, who stated in his speech that,

For de Schweinitz’s time, his research showed its limitations in its assumption that alcohol is the primary factor in many cases he examined. For example, de Schweinitz cited a case that was reported by one of his colleagues. It concerned a 46-year-old man who suffered from diarrhea, so he drank “strong” whisky which resulted in the lower half of his retina detaching [2]. This case was not explored further. At one point, Schweinitz asked why one of his patients named Albert, who drank alcohol and used tobacco for six years, went blind. De Schweinitz and his colleague treated Albert with doses of iodide potassium, nitroglycerin, strychnine, Turkish baths, and silver nitrate, with no success. De Schweinitz went on to say that “there was absolutely nothing in the young man’s history to account for optic nerve atrophy except the abuse of liquor and tobacco” [3]. While De Schweinitz and his colleague recapped the man’s history, they did not consider his family history or test his blood. Their conclusions were merely based on his lifestyle and a physical exam. Alcohol could have impacted the intensity or the timing of the atrophy, but it cannot be assumed that the alcohol was the only cause.

Pertaining to intestinal parasites causing visual disturbances and toxic amblyopia, de Schweinitz discussed twenty-three cases of poisoning in either one or both eyes. The testing was done by Japanese observers, de Schweinitz recounted their experiments and added onto them. This is another instance where de Schweinitz stated that there is no other reason why the participant went blind beside the ingestion of this toxin. De Schweinitz asserted that the amount consumed is not the issue but the toxin itself and he questioned why intestinal parasites cause blindness. “Other than the fact that it is a gastro-intestinal irritant, there is no particular reason from its physiological action to anticipate a selective influence upon the optic nerve” [4]. While he did not have the reasoning behind this occurrence, he was able to discover the toxicity of ingestion which future researchers were able to build on. For case XI, a 29-year-old man was given 32 capsules of 0.25 grams of male fern mixed with pomegranate, an intestinal parasite because it destroys the optic nerve. The participant went blind the next day. There was no follow up noting whether he recovered or not, like in the other cases.

As for marijuana, de Schweinitz described foggy and violet vision after cannabis indica ingestion, but in the cases of acute poisoning there was no research indicating permanent effect on vision. He mentioned cannabis indica being popular in the Eastern countries and instances of rare poisoning. De Schweinitz noted that researching cannabis indica was “foolish experimentation” done by medical students. Pertaining to chloroform, which was then used as an anesthesia for dental work and surgery, there was one case of retinal detachment during chloroform narcosis, but generally the motor and optic nerves are not affected.

As one colleague remembered, “During the many years Doctor de Schweinitz devoted to active practice as an ophthalmologist and to the teaching of ophthalmology, he made many notable contributions to ophthalmic literature” [5]. de Schweinitz paved the way for the modern specialization of ophthalmology, especially understanding of the effects of toxins on eyes and how exposure can cause permanent blindness. Most irreversible toxic amblyopia neuropathy happens in developing children, and in the womb. “In writing the history of ophthalmology in the twentieth century, the work of George Edmund de Schweinitz will stand out with that of other great men like Wilmer and Fuchs. It is certain that the inspiration from his work and character will continue to be a force driving ophthalmology to ever greater heights” [6].

(This post was written for the course HIST H364/H546 The History of Medicine and Public Health. Instructor: Elizabeth Nelson, School of Liberal Arts, Indiana University, Indianapolis).

References:

[1] Clayton Walker, Daniel C. Terveen, and Jane A. Baily, "Nutritional Optic Neuropathy," The University of Iowa Department Ophthalmology and Visual Science, June 12, 2018, https://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/cases/273-Nutritional-Optic-Neuropathy.htm. Chronic alcohol abuse leads to systemic deficiencies in B1, B9, and B12, which then leads to nutritional optic neuropathy.

[2] G.E. De Schweinitz, The Toxic Amblyopias: Their Classification, History, Symptoms, Pathology, and Treatment (Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co., 1896), 26

[3] Ibid., 38-39

[4] Ibid., 217.

[5] C Berens, "In Memoriam–Dr. George Edmund de Schweinitz," Bull N Y Acad Med 1939 Jan;15(1): 59.

[6] Ibid., 60